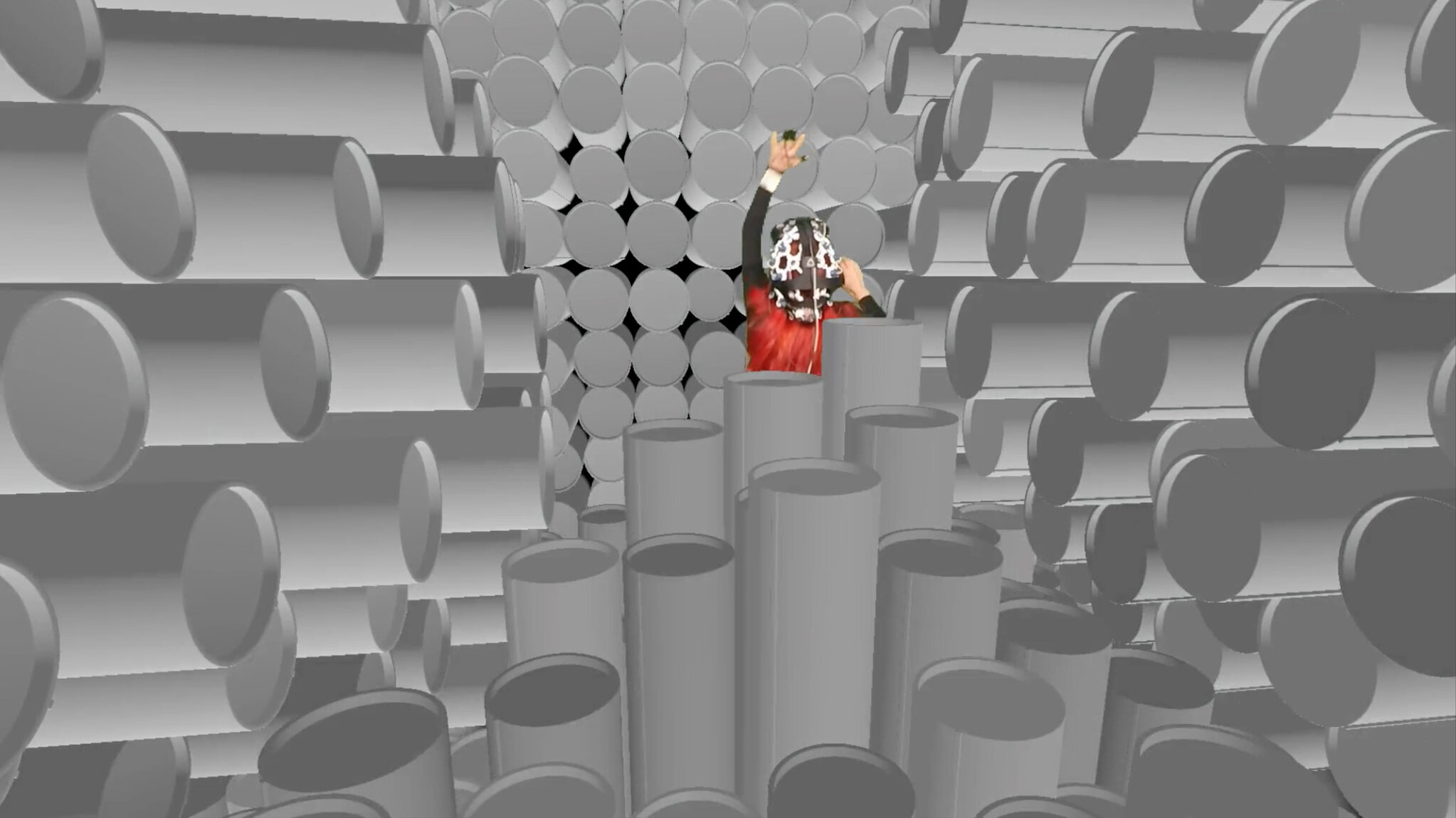

02 INSIDE THE MIND: ULI AP

Alien Artificial Intelligence, 2020. Image credit: Uli Ap

Uli Ap is a transdisciplinary artist working at the intersection of art, science and technology. Ap creates immersive interactive disorienting installations where virtual and physical experiences collide and alter participants' mental states, spatial and immersive video and audio environments to transfer physical experiences through digital realms, destabilising performances to question a post-human condition and levels of reality, AI – VR – BCI – Robotics situations.

Her recent works include the creation of experiences which immerse participants in distorted spaces and conversations with the Alien Artificial Intelligence; and techno-dystopian pushing the boundaries installation ‘Anti-Gravity Reality: Inside the Black Cube or Brain AI’, which combines a physical robotic space of moving elements with a virtual reality headset, enabling participants to literally build a ‘virtual room’ while wired up to sensors where ‘emotion detectors’ control the resulting environment.

Here we discuss how an artist’s interdisciplinary background can inspire their creative process, allowing for various tools to be utilised when deconstructing abstract themes. We additionally explore the concept of multiple realities and how artists can utilise and repurpose artificial intelligence and biotechnology such as electroencephalography (EEG) and galvanic skin response (GSR) or heart-rate/pulse sensor (HRV) to create immersive installations that simulate multisensory experiences. Resulting in a reflection on the loop this creates between the artist, installation and audience participants.

Dwaynica Greaves (DG): You have described yourself as ‘working at the intersection of art, science and technology.’ How did you begin your practice in each of these fields? And how have you interpolated them?

Uli Ap (UA): My father is a scientist and engineer whose lab was in the basement of an art museum. As a little kid, I used to spend time playing with computers in the lab and going upstairs to see the artworks. I also interacted with a lot of scientists outside of the lab because I would see them at home. Then, I moved into studying fine art, new media art, and architecture to investigate technology and space. Simultaneously, I worked as a fiction writer and journalist. As all those different experiences are part of me, I thought it makes sense to combine them to create my own unique art practice. I wanted to be the first ever ‘Uli Ap’ with all these different fields, coming from different areas.

I do not practice each of these areas separately. I collide them to build immersive environments which disorientate people between disciplines, levels of reality, their own perceptions, and make them to question or reinvent their own self. Inventing contradicting or provocative concepts, I create a cross-reality zone between opposing forces and in that zone is where I operate. I enjoy disorientating and challenging people to question established norms or accepted realities. I think I can do it because I have access and experience into all these different fields.

DG: Could you tell us more about the benefits of using multiple fields to explore concepts such as ‘post-human self,’ seen in your work titled ‘Red Salt Bath’?

UA: ‘Red Salt Bath’ is about deconstructing scientific truths. It is an experience where people enter a volumetric space in VR that is constructed of defragmented words of scientific papers. Using EEG and their own bodies, participants could pull and push and displace words from scientific papers interactively. This process results in the manipulation of the meaning and construction of their own truth. This is technically what artists do: we mess everything up and create strange constructs that people cannot decipher.

Red Salt Bath, 2014. Work includes text from papers by Joseph E LeDoux: ‘The Slippery Slope of Fear’, Trends in Cognitive Sciences April 2013, Vol. 17, No. 4. and ‘Coming to Terms with Fear’, January 9, 2014, PNAS | February 25, 2014 | vol. 111 | no. 8 | 2871–2878. Image credit: Uli Ap

I put people in a position where they can build up their own realities by deconstructing scientific research, which I have done by here by reinventing the exhibition format and inserting participants in the centre of an interdisciplinary collision. The project questions every truth that is delivered to us because there are so many statements we have from media, news, publications, philosophy and science that we take for granted and without question. This project explores if we could be able to create our own post-human truths.

The ‘post-human self’ is a state of being beyond human. In a way, it is a state when you are neither human nor machine. We are equipped with so much technology that we are now dealing with issues of transhumanism. People may have high-tech implants where body parts are displaced or changed with help from artificial intelligence. We are a post-digital, post-media society, where we are merging with machines to become… – but whom will we become? This is a question. I attribute machines to scientific and engineering research, because scientists and engineers create the machines that we interact with, work with and live with. At this moment, I do not think we can imagine ourselves without machines. Without our phones, for example, we feel lost and disconnected from the whole of society. So, when I make people interact with scientific articles, I put them into contact with the source of our machines, where our post-human selves came from.

Ultimately, the advantage of using multiple fields in my work is that concepts such as the ‘post-human self’ do not exist in one field. I think society over-emphasizes the notion of singular fields: the message I’m constantly projecting is that there are no disciplines anymore. This is because people continuously cross disciplines. I myself am a very hybrid artist, and I see interdisciplinary approach in scientific institutions which bring together a variety of individuals across different fields. Especially when working in complex realms, such as artificial intelligence, a multitude of fields merge.

Our post-human potential is constructed and mediated through technological advances that are, in effect, very trans-disciplinary. Technological constructs around us become us to a certain extent.

Staircase, 2013. Staircase, monofilament. Interactive Installation. Spaces changes itself as you move. View towards the sky. Image credit: Uli Ap

Staircase, 2013. Staircase, monofilament. Interactive Installation. Spaces changes itself as you move. Detail. Image credit: Uli Ap

DG: Looking at some of your other projects such as ‘Staircase’ (2013), ‘White Light Inside the White Cube’ (2015), and ‘Talk to Me’ (2013), the concept of ‘space’ is frequently mentioned. Why is ‘space’ important to your practice? In what different ways do you explore ‘space’ across these projects?

UA: These projects reflect my belief in having new art experiences that activate all your senses, something that engages everything inside and outside of you rather than making you look at one singular whatever. I construct spaces and unexpected experiences in those spaces to create an entirely immersive situation where your intellectual, emotional and bodily experiences converge – a situation where you question your own ‘self’ and different realities that exist, including Virtual Reality. It is to explore a paradox of immersion and interaction through disorienting, defragmenting and distorting installations and environments.

Space behaves differently in each of these three projects.

‘Staircase’ is a space that is simultaneously present and absent. The installation is constructed from transparent monofilament which is activated by light at different times of the day and at different angles. Your perception of the structure changes with your position on the staircase. Your individual experience is never the same as another’s’, and each of your single experiences will be different too: walking on the staircase at different times of the day within different atmospheric conditions or late at night with artificial lighting, while having certain bodily proportions, which are mainly important because of the position of your eyes, results in different experiences. At times, some parts would be hidden from you, while others would appear denser. Moreover, with every step, perspectives open up differently. Being the same structure – it is never the same structure.

‘White Light Inside the White Cube’ is a project that questions a gallery space as a sacred space of contemporary art. The White Cube is 2 x 2 meters, but due to the brightness of its environment you do not feel the borders. Instead, you feel as though you are in an infinite space. Then, there is a character with an erased identity – ‘The cReature’. ‘The cReature’ is also fluorescent white, so it merges with the environment and becomes unseparated from its surroundings, transparent and non-existent.

In contrast, ‘Talk to Me’ is an environment that creates distortions of space and the self that navigates the distorted space. It is a project about the impossibility of conversation, how conversation can become deformed, not heard, non-existent. Furthermore, a combination of sharp blue fluorescent light and reflective silver insulation foil will make you feel dizzy – if you stay in space for more than half an hour.

Talk to Me, 2013. Five-room immersive environment. Aluminium insulating foil, blue fluorescent lights, windows, space, two-way mirrors. Image credit: Uli Ap

Talk to Me, 2013. Five-room immersive environment. Aluminium insulating foil, blue fluorescent lights, windows, space. Image credit: Uli Ap

DG: This explanation of your three projects is fascinating, specifically how you utilize materials and light to explore ‘space’ within the foundational theme of each piece. Your point about the single experience being different for each individual leads me to the next question: can you tell us more about the audience responses to the spaces in your work? Are there differences in the way they manoeuvre and interact with your installations?

UA: My audience experiences are different because my materials and concepts are different. This is because I hate repetition – I want every project to be different. Mainly because it gives me different experiences working on them. Ideally, I prefer to be in different countries and locations with different people all the time to see how those environments and experiences will change my artistic processes and what it triggers within me as an artist.

White Light inside the White Cube, Art Licks Weekend, 2015. Live 3-Day Performance inside the immersive disorienting installation White Cube during the Art Licks weekend, 2015. Multichannel video installation with thirteen episodes. Image description: Episode 1: Fear. The cReature in the embryo pose. Hugging. The space is brightly lit so that you feel neither its borders nor its presence.

Each project explores a new territory. Although, it may be something I don’t know or am terribly uncomfortable with. I will dive into it, explore it, learn and construct a project out of it. I like to search for new meanings and expressions in art while constantly reinventing myself, exhibition formats, and pushing the boundaries of what is acceptable in the arts. I want to challenge and change art by bringing something that hasn’t been previously done, something new.

Each person has a different experience and interaction with my installations. Experiences also differ in how people interpret the installations, which is affected by individual background and what the environment triggers in one’s intellectual processes, bodily reactions and emotional responses. This becomes the basis of the experience.

Hence why I prefer for people not to know of my artistic intentions behind the creation of artworks prior to the experience, because they will be guided by my voice, as the authority of the artist, and they would filter their experience through me. It is better if they know only after the experience because ultimately, I want them to be in the situation and make the experience their own, and hopefully it would change something in them. I want to give them an experience that they would not have come across otherwise (in daily life or other artworks). To give them an experience that becomes like a little event in their reality, which changes something in them, while simultaneously being a part of them.

DG: Neuroaestheticians have found that aesthetic experiences are affected by individual differences such as expertise and life experiences; hence, the multiple intellectual and emotional triggers that lead to an individual’s interpretation of an artistic piece. We have discussed the ‘physical distance’ between the audience and artwork but there is another concept of interest called ‘psychical distance’: the intellectual distance between the artwork and audience due to the knowledge that there is an element of the art piece that is not the same as everyday reality (Bullough, 1912). Psychical distance is said to intensify aesthetic experiences. What are your thoughts on these concepts, reflecting on your work?

UA: As an artist I break physical distance because I want people to touch my installations. I find this amazing to observe because people have been conditioned to think that there should be distance between themselves and an artwork. So, I feel like I have to put up very big signs that say ‘please touch’ or ‘please interact’ because people are afraid to. However, the opposite also happens when you tell people they can touch, and they do it so much that I end up having to repair parts of the installation.

Perhaps, my decision to remove physical distance originated from my own experiences of going to museums, where I would see great paintings but have to maintain distance due to preservation regulations. I thought this degraded my experience because as an artist I want to get really close to paintings to see the structure – like how Renaissance masters use glazing, and how light hits each of the layers. But you can’t traditionally do this in a gallery, or you will trigger an alarm and security guards will appear. This is not the way I prefer to view an artwork. It feels, constraints of the traditional gallery experience influenced how I construct my installations, which is to encourage people to break this physical distance. Paradoxically, breaking a physical distance in centimetres through interaction, dramatically increases a physical distance in our intellectual processing. Simply because the environment you enter is so unreal.

Artificial Intelligence of Virtual Reality, Ambika P3, 2019. Two-channel video projection of That Side Where Real Is at Crypt@St Marks’. St Marks’ Church, Kennington. Human element enters alienated space of the cReature. Installation view at the room adjacent to the main floor. Image credit: Uli Ap

Before the invention of the abstraction, psychical distance referred to whether a painting was a depiction of reality or an artwork. With performance it is a difference between a ‘dramatic performance’ which may be ‘not likable’ but is an artistic or aesthetic experience; and something that ‘is likable’ but is empty of art value. The quote I grabbed from Bullough’s 1912 paper was “It renders questions of origin, of influences, or of purposes almost as meaningless as those of marketable value, of pleasure, even of moral importance, since it lifts the work of art out of the realm of practical systems and ends”. To me, reducing the psychical distance in spatial dimension and increasing physical distance in intellectual dimension, is important because when you deal with installations people try to find some practicality, which is not there.

DG: Referring to your last statement ‘people trying to find some practicality’ could you explain what you mean by this, and how this affects how you approach your work?

UA: Sometimes referring to contemporary art, people think that an artwork is meant to solve a social problem, act as a cure, or hold a purpose beyond art. My statement is that there is no such purpose –the purpose of an artwork is an experience, the inner most value of an immersive work of art is the experience. I need to push into this because it is quite tricky to explain to people why there is no purpose.

I don’t construct objects - I build experiences which are experiences for their own sake. It’s like how Lebbeus Woods describes his ‘Light Pavilion’, he states that this is an ‘experimental space’ and ‘as transient inhabitants we shall simply have to go into the space and pass through it, perhaps more than once’ because ‘our rapidly changing world constantly confronts us with new challenges to our abilities to understand and to act, encouraging us to encounter new dimensions of experience’.

I would say that even constructing the artwork as an artist is like becoming non-human. The artist encounters all kinds of constructed realities. Even everyday reality is a construct and not real to a certain extent. Then you find yourself in an immersive experience and you are totally disoriented between these different realities. I also think it’s because art is becoming non-static, moving past objectivation and being perceived outside of our bodies, drawing us in through the whole experience. Art is 100% a reality-bending solution. It modifies and bends reality, which does not exist anyways – what are your thoughts on that?

DG: Interesting question - I think that when I make artwork, I am inspired by reality, but I am also merging realities which creates a new reality for the artwork. But breaking the realities that we know into constructs for the purpose of creating a new construct does not make the artwork less real, that may make it more grounded. This is a perfect segue to your installation ‘Anti-Gravity Reality: Inside the Black Cube or Brain AI’ at Ambika P3, as it also explores multiple realities and the psychological transmissions between audience and installation. It is described as, ‘… a trans disciplinary encounter between Virtual Reality, Artificial Intelligence, Robotics, and Neuroscience that reinvents human relationships with a machine – to construct art without artists and architecture without architects.’ What relationship between human and machine did you aim to achieve?

Artificial Intelligence of Virtual Reality, Ambika P3, 2019. Solo exhibition in partnership with The University of Westminster. And London Festival of Architecture. Installation view on the main floor. Image credit: Uli Ap

UA: My solo exhibition at Ambika P3 ‘Artificial Intelligence of Virtual Reality’ explores the transitional space in-between physical and digital reality.

Artificial Intelligence of Virtual Reality, Ambika P3, 2019. Solo exhibition in partnership with The University of Westminster. And London Festival of Architecture. A participant’s interaction with Anti-Gravity Reality: Inside the Black Cube or Brain AI. Installation view on the mezzanine floor Image credit: Uli Ap

I also tend to add mental constructs to this physical-digital transitional space because I want people to be disoriented by the nature of the experience. Is it a product of their brain, imagination, physical, virtual field or is it a transcendental dimension? I am interested in a conversation about multiple dimensions and how many dimensions our brain can perceive. A while ago there was a paper which revealed that the brain can construct structures in 11 dimensions. It really strikes me as the idea of additional dimensions is fascinating to me.

So, with ‘Anti-Gravity Reality: Inside the Black Cube or Brain AI’, there is an exchange between humans and machines: humans become machines and machines become human. Artificial Intelligence becomes ‘a human’ by becoming emotional, while humans lose their ability to feel. It happens because Artificial Intelligence borrows or steals human emotions, constructs itself through them and constructs the spaces it inhabits in order to become emotional itself. By “digesting” “consumed” “emotional data” of a singular individualised “human element”, AI algorithm creates itself and an environment of its own habitation that is its own self.

What happens in a project like this is that the human brain constructs highly individualised experiences in Virtual Reality (VR) as participants wear a VR headset coupled with EEG. This personal individualised interaction between human and machine modifies what the human experiences in both VR and the physical space simultaneously. When you touch a virtual shape, it expresses force and resistance and feels tactile. Therefore, Virtual Reality becomes Physical.

However, as virtual and physical spaces are mapped onto each other, participants never understand which is which: some virtual elements deliberately are not mapped onto the physical machine. Hence, participants struggle to understand what is physical and what is virtual. By embracing this experience, they are merging with the reality of the machine. Although, they don’t understand what the machine is constructing, what they themselves are constructing, what is part of their imaginary experiences, what is manipulated or who is manipulating what. Because the individual doesn’t understand the extent to which they are in control, they become confused and disorientated.

DG: It’s fascinating seeing how the various elements to the installation could produce so many questions during the audience experience that their cognitions could become analytical as well as exploratory. To unravel the description of ‘Anti-Gravity Reality: Inside the Black Cube or Brain AI’, what did you mean by ‘art without artists and architecture without architects?’

UA: After the interaction people can explore the physical spaces they created. A virtual space of the interaction is also recorded dynamically and available to participants as a 3D print or dynamic CGI system. Then, the AI combines each personalised individual structure (i.e., experience) from every participant recorded over duration of the exhibition and synthesises them into one collective generalised structure. This is the reason why I say it’s art without artists because people are using their emotional reactions to generate art.

Anti-Gravity Reality: Inside the Black Cube or Brain AI, 2018. Inside VR. Interventions. Living AI organism consumes human emotions. (anxiety) in order to acquire feeling and construct spaces in physical and virtual domains. Participants create their highly individualised experiences with their own brains.

Image credit: Uli Ap

In this iteration I used anxiety to trigger individual experiences. It is deliberately controversial. The machine provokes this anxiety which people respond to, and the way they respond dynamically alters the environment that they experience. This is why every person encounters a different situation, and it’s the reason why one's emotional state will result in a unique exhibition experience. This process creates highly individualised experience, data of which is later analysed by AI to synthesise it into a collective generalised structure – a collective anxiety pavilion.

Anti-Gravity Reality: Inside the Black Cube or Brain AI, 2018. Inside VR. Interventions. Living AI organism consumes human emotions. (anxiety) in order to acquire feeling and construct spaces in physical and virtual domains. Participants create their highly individualised experiences with their own brains.

Image credit: Uli Ap

It can then be experienced in Virtual Reality as an entirely separate experience. My intent is to extend the installation into a pavilion that people can physically enter and explore. Then, I would be interested to see the different responses of people who have either been with the project since the beginning and contributed their emotions to the AI generated constructs, versus others who have just entered the already constructed anxiety pavilion, and how these different groups relate to each other. This is why I say its architecture without architects - because every person becomes an architect: through their emotional reaction they create a physical structure or a pavilion. The pavilion is a construct of all the participants who contributed to this technological anxiety experiment. And they turn into artists because they alter their own experiences of the artwork with their own brain throughout the process.

DG: I love this explanation! When I initially wrote the question, I was intrigued as to how that could be so, but now I understand that it goes beyond the abstract thought of ‘everyone is an artist’. You also touched on the different dimensions you explored i.e., Virtual Reality, Physical Reality and Mental Space and the audience's disoriented experience. Hence my next question is, what is your opinion on the similarities and differences between VR and physical reality? Also, did the audience participants have any interesting comments on the experience?

UA: When I started working with VR, I realised that I was really drawn to the medium not for the sake of itself, but because it appeared to be as immersive as my own environments. The trick your brain does while navigating VR space makes you feel that Virtual Reality is the same as Physical Reality – as for your brain there is no difference between the two.

I found it fascinating, but I also felt it wasn’t enough. There was something missing: sensations such as touch and smell that act as components of immersion in physical spaces. Pursuing a disorientation, I came up with an idea to collide virtual and physical space. And their behaviour to be interchangeable: virtual space does not have a gravity; therefore, physical space does not have it either. But I also didn’t want people to understand which is which.

Anti-Gravity Reality: Inside the Black Cube or Brain AI, 2018. Inside VR. Interventions. Living AI organism consumes human emotions. (anxiety) in order to acquire feeling and construct spaces in physical and virtual domains. Participants create their highly individualised experiences with their own brains.

Image credit: Uli Ap

I really didn’t appreciate the idea of touching something in the virtual space, feeling like it might be real – then touching your own hands, and braking the immersion. I wanted people to touch the virtual space and believe it’s real or physical.

When this happened, what I’ve seen from people’s reactions is that they are really shocked. Especially when they enter the exhibition, they don’t see the physical structure as yet. They think that all that they experience is inside a VR headset. Then, all of a sudden, they feel force and resistance, a tactile sensation that leaves them shocked, frightened and inquisitive. Additionally, some virtual elements are identical to physical elements, and some are not. So, when people touch the virtual elements that are connected to physical elements, they feel the physicality. However, if a virtual element is not mapped to a physical reality, then it escapes their touch. So, they never know.

A virtual element either moves towards a participant or comes away from them. As a result, people don’t really understand what is physical and what is virtual. They also don’t understand how this interaction happens. It makes some really excited and enthusiastic: they try to touch everything, build something in places where nothing is there, or even try to find the logic behind it. One participant was trying to build the letter ‘A’. Some people want to interact several times, because they want to crack the interaction and find the logic within it. The environment is additionally confusing given the ongoing sound of the participant’s heartbeat, brain-wave activity and my other installations. Also, with heartbeats – participants manipulate my pre-recorded heart-rhythm with their own heart-rate. It is an exchange between me and them; and them becoming me, inhabiting my body or brain, or creative processes.

Anti-Gravity Reality: Inside the Black Cube or Brain AI, 2018. Post-human. Image credit: Uli Ap

By the way, the person who built the letter ‘A’ took several trials to build it. It was never my intention for them to build something concrete, but people do it. I find this amazing because this is how individuals interpret the project differently and bring their own personalities to it.

When I am present in a space, people really want to talk about it, because they want to know what happened to them and they want to share their experience. My participants become performers as they do very performative actions. The more people are drawn to such experiences, the braver they become, and further exploration becomes like an improvised performance which is recorded by the machine that uses a surveillance principle in its defragmented manner.

In the ‘Brain AI’, everything is set in motion: unknowingly, audiences are turned into performers in a performative space that is orchestrated by their own emotions.

One of the comments that stays in my mind: a participant told me that they felt robbed of anxiety completely, that now they are very happy because the machine stole all the anxiety and it will make the world a better place if loads of these machines are installed.

Therefore, this project needs to be experienced for one to get something out of it. Perhaps it is possible to understand the project on an intellectual level but to fully appreciate it one must have the literal individual experience. It goes under your skin, and you feel strange sensations that you cannot feel through documentation. That is how I feel about all of my works.

DG: The delegation of anxiety to the machine is a striking phenomenon, especially since you stated earlier that your art is for the purpose of experience. Nevertheless, participants feel a relief after experiencing your installation. I’m intrigued to know why you chose anxiety - what was the creative reasoning behind this choice?

UA: There is no purpose…

Fears and Anxiety are fascinating. Especially, today’s technological anxieties, the ones provoked by a machine.

In the construction of the experience, I draw a lot on research of Professor Joseph E. LeDoux, and Professor Lisa Feldman Barrett’s Theory of Constructed Emotions. The theory proposes that emotions are not reactions to but rather constructions of the world, and that emotions are the whole brain-body phenomena, not just of the brain alone, and therefore should be perceived in its entirety.

‘The theory of constructed emotion proposes that emotions should be modeled holistically, as whole brain-body phenomena in context. Emotions are constructions of the world, not reactions to it. In the theory of constructed emotion, a concept is a collection of embodied, whole brain representations that predicts what is about to happen in the sensory environment.’

My creative decision to elicit anxiety was intended to create a paradoxical situation where one’s anxiety is actually provoked by the machine. The cube does everything to disorientate you and make you feel uncomfortable and anxious. It thus generates your anxiety to power itself up with it. Then, you donate or delegate your anxiety to a machine. This is a way you cope with your anxiety. So, it is a loop in which everyone is entrapped. There is no escape.

The anxiety is both caused and removed by artificial intelligence which for now holds society in a state of panic. Fear and Desire of a machine…

The fear people have of machines robbing their jobs and ending everything. To me, this fear is the same as in the 15thcentury when people were panicking due to the invention of printing as they thought no one would write by hand anymore. Similarly, when Kindle was invented, everyone thought people would forget how to read paperback. No one forgot anything, it all continues but some things just make life easier or different. I think the same will happen with AI…

DG: On the topic of the audience's emotional states affecting their experiences with your installation, my next question is something I have previously thought about when conducting my first research project on the effect of emotions on aesthetic perception, which definitely links with what we are talking about. Do you think it’s important for audiences to be aware of their psychological states when interacting with art, given that one’s psychological state can affect perception and interpretation of art across different styles?

UA: I don’t think they need to be aware of it. I think it causes the same effect as reading what an artist says about their work before seeing their work. It’s better if they understand the processes of the experience at the end. I would rather let the audience have the experience, then disclose to them what actually happened and what was involved – as post-factum. I would prefer for them to not think about anxiety, to not read anything about it, but instead to just dive into the artistic experience freely. From an artistic perspective this creates a richer experience. What do you think?

DG: From a neuroaesthetician’s perspective, I would agree. This allows the audience member to reflect on how their psychological state prior to the experience may have influenced their interpretation of things, and further encourage them to experience the piece multiple times to compare experiences. On the topic of research, you mention the use of electroencephalography (EEG) and galvanic skin responses (GSR) which are popular tools in the neuroaesthetician’s arsenal. When did you first become introduced to biotechnology and how did you repurpose these machines for your installations?

UA: I first encountered EEG when I was in a conference ‘Meeting of the Minds’ at Imperial College London. I became obsessed with EEG, and Imperial College connected me with neuroscience societies across London universities.

In the ‘Brain AI’, the manipulation that happens through these biosensors with the assistance of the AI organism generates a dynamic and synthetic environment which is constructed by your own brain. Referring to the Theory of Constructed Emotions, I decided to connect the EEG with other biosensors that can read and collect emotional responses all over the body.

The signals from GSR and heart rate feed into the EEG which manipulates the whole environment. Because this project explores contemporary anxieties related to fast paced technological advances and the condition of being post-human with these anxieties, our emotions and feelings are consumed by this living AI organism in order to create itself in virtual and physical realms.

The post-human combination of sensor networks enables highly personalised experiences by passing the collected data to virtual reality, and then the robotic machine. Ultimately, the machine is activated by your personal data. It’s like a biological and digital unity because you merge with the artificial environment and exchange with it.

DG: Moving away from the mechanics of your installation, I want to discuss artistic choices you made in the documentation of your installation. The first video demonstrating the participant experience allows us to visualise the virtual and tangible reality at the essence of the work. The text within this video includes the phrase ‘brain AI = emotional AI, reality is mental’. What does this mean? How does this apply to reality outside of the project – in today's world, or maybe ‘tomorrow’s’ world’?

UA: This statement deals with my obsession of creating emotional AI and seeing what happens when AI becomes emotional and how it will change the behaviour of algorithms. As for now, the algorithms are logical and structural, I asked myself, ‘would emotional AI be prone to mistakes and imperfections, would the algorithm make emotional instead of logical decisions?’ ‘Would it suddenly run out of control and offer you something bizarre as a mistake, as people do when we are emotionally involved in something?’ So, I began to test this ground to see if it is possible for AI to feel this way.

‘Brain AI’ is when your brain is merged with AI, and by doing so it becomes not your brain but the AI’s brain or AI Brain becomes your human brain. It is a provocation: AI is constructed using the human brain as an analogy.

‘Reality is mental’ deals with the fact that everyday reality is a construct: it’s not real. You can trace these theories back to Buddhism. Because this project deals with a reality that is neither virtual, nor physical, nor a construct of your brain, it makes the experience even more unreal and surreal as it’s not categorized in any tangible way. A complete phrase is: reality is a mental construct. Which means that reality is constructed by your own brain.

Back to the second half of your question about how this can be applied to today’s and tomorrow’s world: our emotions and personalities may be discernible by these complex sensor networks, allowing for the construction of individual experiences that may communicate with us on our subconscious level. An example could be in architecture - maybe one day we’ll be able to design houses through our emotions, rather than verbally communicating with architects. There could be dangerous implications of these technologies if misused in other fields such as the military, but such tools are great to experiment with in creative processes. And one simply can’t ignore them as living today artist.

DG: It’s certainly very interesting to contemplate how the brain may be able to connect with AI in the near future in order to facilitate or even drive creative decision making. With regards to artistic practice, my next question is about other mediums outside of the visual medium that you use in your work. In the third video showing the ‘Black Cube’, you have a voiceover with animations of poles and triangles inserting themselves into the box. What was your creative process when it came to utilising the medium of sound in your work?

UA: ‘Black Cube’ is an expansion of Kazimir Malevich’s ‘Black Square’ into space. The sound in this piece is Malevich’s ‘Suprematism Manifesto’. The situation inside the ‘Black Cube’ is a homage to Zaha Hadid and her anti-gravitational floating spaces.

In my work sound is very important, but it’s not always a voice. My installations themselves generate sounds during interaction. I tend to record these sounds, so I can I make expositions of them: an installation of the sound alone, without any structures in space. Just an empty space and sound. Thus, people can experience the installations through sound. It becomes the experience of a space as an absence of a physically constructed space, and a presence of a sound. A space constructed by sounds and/or voices.

I’m also interested in observing the differences between people who have seen the original installations and people who have only experienced those installations as sounds or interactive soundscapes. I explore the translation of one experience into another, of transferring a disorienting physical space or destabilised performance through sound and digital technology.

In the ‘Brain AI’, at the interventions, there are sounds of some of my previous installations that have been recorded, such as ‘Sacred Danger’ and ‘That Side Where Real Is’. These are very intense, dense sounds, sounds that are present in this highly technological construct to maximise your anxiety.

DG: As you mentioned, the voiceover is a reading of Kazimir Malevich’s ‘Suprematism Manifesto’. A quote I found very intriguing was ‘…it wants to have nothing further to do with the object but wants to exist for itself…’ This statement is about art and it makes me think of art as separate from its creator. Do you believe that we are using art or that art is using us?

UA: The ‘Black Square’ is an invention of an absolute abstraction that is reflected in ‘Suprematism Manifesto’ as a rejection of narrative structures in order to search for something beyond the physical world. It wants to exist for itself as a pure form referring to abstraction, qualities of the paint itself and the spiritual meaning of art. “By ‘Suprematism’ I mean the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling."

The ‘Black Cube’ wants to invent an absolute environment. It takes our biological data (feelings and emotions) as a source material to create art. However, I do not think anyone is using anyone – it is all a process of exchange and interaction. A while ago I used to call a visitor or participant a ‘human element penetration’, which drove everyone mad and someone even said that it sounded very mean. But humans penetrate the installations, activate them, generate sound in them, and have their own experiences in them – so they are, indeed, human element penetrations!

Entering the ‘Black Cube’, humans directly benefit with having new experiences in return for donated emotions to a machine and become abstractions: almost like a material of the installation in this way. ‘Human element abstractions’? In the context of the ‘Brain AI’, I can probably say that my materials are sensors, actuators, hardware, software and human emotions.

DG: You can definitely say that you used human emotions as a material for your installations. It’s a very interesting way to look at how we identify our materials when making art. To end, I will create a full circle of this discussion and bring us back to the ‘cross-reality zone’ you mentioned in the beginning. Furthermore, your bio states that you ‘believe in a world with no borders and no identity’. Can you explain what a ‘cross-reality zone is’ and lastly, as we have been speaking about transdisciplinary work and multiple realities, how do you define ‘border’ and ‘identity?’

Oxford Street Alienation, 2020. Live Performance. Image credit: Uli Ap

UA: The cross-reality zone to me is a world that blurs the digital with the biological and physically or mentally constructed. Where physical becomes virtual and virtual becomes physical. I do tend to extend it to mental spaces and transcendental spaces. From a scientific point of view, the concept of a cross-reality zone originates from ‘X Reality’, which then was extended to ‘cross-reality’. The term ‘cross-reality zone’ was coined by Professor Joseph Paradiso and James Landay. According to their research, cross-reality is location specific – real situations and 3D animated constructs are put in the virtual world, around which a sensor network is built. “We define cross-reality as the union between ubiquitous sensor/actuator networks and shared online virtual worlds – a place where collective human perception meets the machines' view of pervasive computing.” The work surrounding cross-reality zones has evolved and transformed with the use of immersive technologies that are systems enabling virtual reality, augmented reality, mixed reality, cinematic reality or any kind of transition in-between that allows you to mix up hardware, software, sensors and actuators with virtual spaces to bring physical objects into digital environments or digital objects into physical reality and facilitate complex and dynamic experiences.

Identity does not exist. It’s a social construct. By default, there is nothing that identifies or distinguishes us from each other or restricts us to particular locations. By default, we are free and unidentifiable. To me, to identify something is to enclose it in its borders, but there are no borders. Because all borders are open. There are no geographical borders: they are as identities socially constructed. We should be able to be anywhere any moment we want. There are no disciplinary borders. There are no gender borders. Everything is fluid. No one rules no one. No labels mean no compartments. No more describing something with one word or labelling because things have become much richer, more dynamic, more trans. We are neither, and both at the same time. There are no borders and identity is fluid. Everything is transgressing, transforming and evolving constantly. As humans, we cannot detect these changes because everything changes so quickly and intensely. We all should become Alien Artificial Intelligence to contemplate this process.

For more on Uli Ap, please visit: http://uliap.art/

References:

Ap, U., 2019. Red Salt Bath. [online] Uliap.art. Available at: <http://uliap.art> [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Ap, U., 2013. Staircase. [online] Cargocollective.com. Available at: <http://uliap.art> [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Ap, U., 2013. Talk To Me. [online] Uliap.art. Available at: <http://uliap.art> [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Ap, U., 2015. White Light Inside the White Cube. [online] Uliap.art. Available at: <http://uliap.art> [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Ap, U., 2018. Anti-Gravity Reality: Inside The Black Cube or Brain AI. [online] Uliap.art. Available at: <http://uliap.art> [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Ap, U., 2019. Artificial Intelligence of Virtual Reality. [online] Uliap.art. Available at: <http://uliap.art> [Accessed 7 December 2020].

Barrett, L.F. (2017) How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. Macmillan, New York, London.

Bullough, E. (1912). “PSYCHICAL DISTANCE” AS A FACTOR IN ART AND AN AESTHETIC PRINCIPLE. British Journal of Psychology , 5(2), 87–118.

LeDoux, J. E., & Brown, R. (2017). A higher-order theory of emotional consciousness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(10), E2016–E2025.

Front. Comput. Neurosci., 12 June 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fncom.2017.00048

LeDoux, J.E. (1999) The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. Phoenix, London.

LeDoux, J.E. (2003) Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are. Penguin Books, New York.

LeDoux, J.E. (2016) Anxious: Using the Brain to Understand and Treat Fear and Anxiety. Penguin Books, New York.

Picard, R.W. (1997) Affective Computing. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

All images shown courtesy of © 2021 Uli Ap