0RPHAN DRIFT: CAN OCTOPUSES CHANGE OUR WORLD?

What is it like to be an octopus? Would that be a better model for how an AI might be regarded as ‘intelligent’ than assessing how its responses differ from the human? And what would that mean for the way people look at the world? The collaborative artist 0rphan Drift has recently captured the attention of both scientific and artistic communities by exploring such questions. I spoke online to Maggie Roberts, who is spending lockdown in a studio in South Africa, but normally spends most of her time in London.

0rphan Drift made their first impact in a different era, responding to machine-human interaction in the time of cyberpunk and the birth of the internet. Founded in London in 1994, it operated as collective of four female artists – Maggie Roberts, Ranu Mukherjee, Suzanne Karakashian and Erle Stenberg – exploring the interface between the actual and virtual through fictioning and attempts to expand into the unknown. The name doubles up on fluidity: moving forward without a backstory (‘0rphan’) on an unplanned course (‘Drift’) – and that’s an integer, not a letter, up front, a machine code reference which also hooks in Sadie Plant's book Zeros and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture (1997). The irony of the name, says Roberts, was that by 2003 the collaboration artistically drifted, core members moving to focus on individual practices in their native countries of the USA, Spain and Norway, while only Roberts remained in London. In 2006, though, she and Mukherjee restarted as a duo, believing that 0rphan Drift’s approach could be tellingly applied to the new era of social media, Artificial Intelligence and virtual reality. In its latest manifestation, 0rphan Drift considers AI through the octopus – as a distributed, many-minded consciousness. Several inter-linked projects suggest the possibilities, says Roberts, ‘for inhabiting other systems of perception and proprioception, combining video, animation and text to suggest new spatio-temporal formations and ask what kind of bodies might be possible with the new coordinates suggested by VR or VFX animation.’

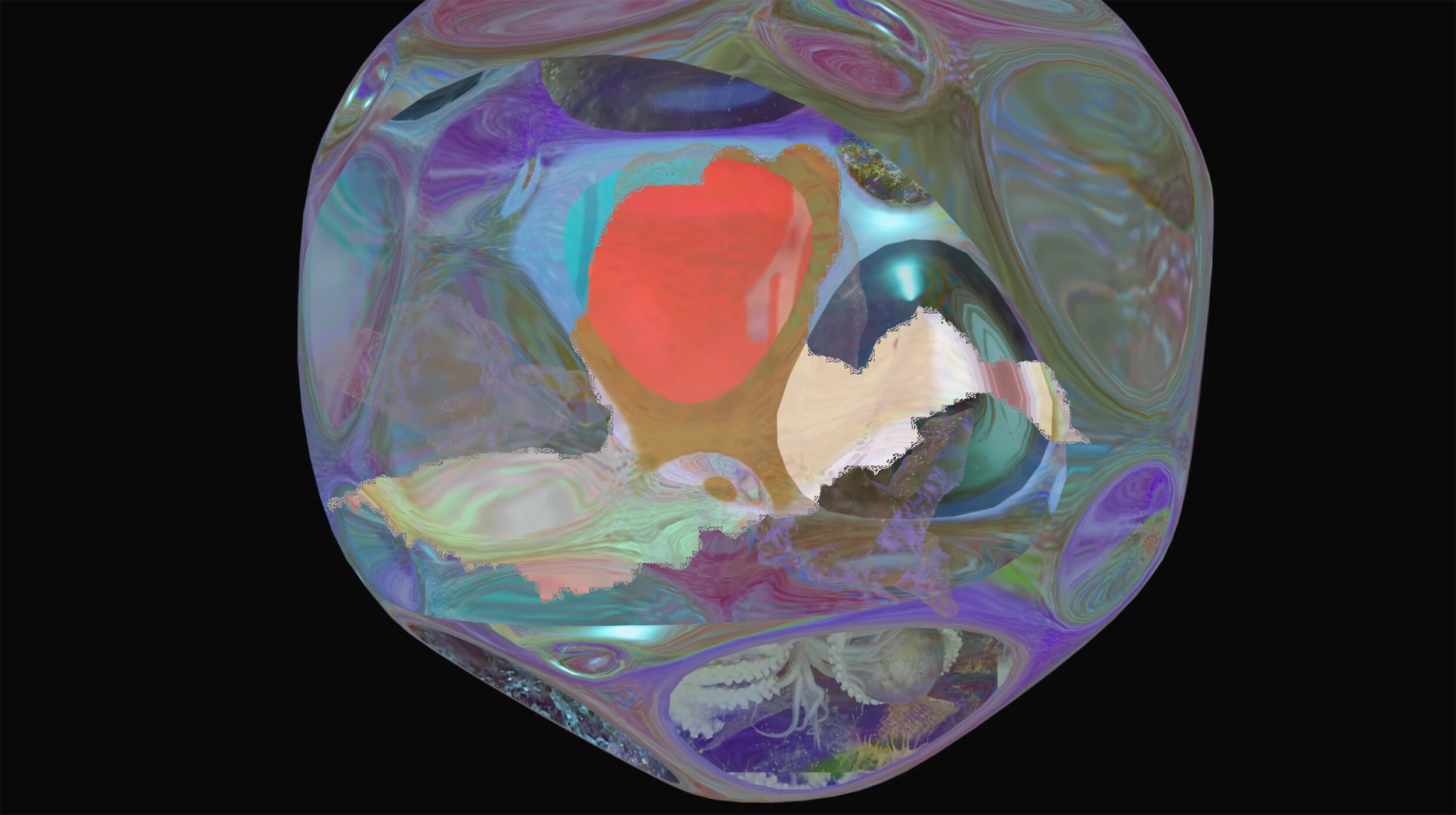

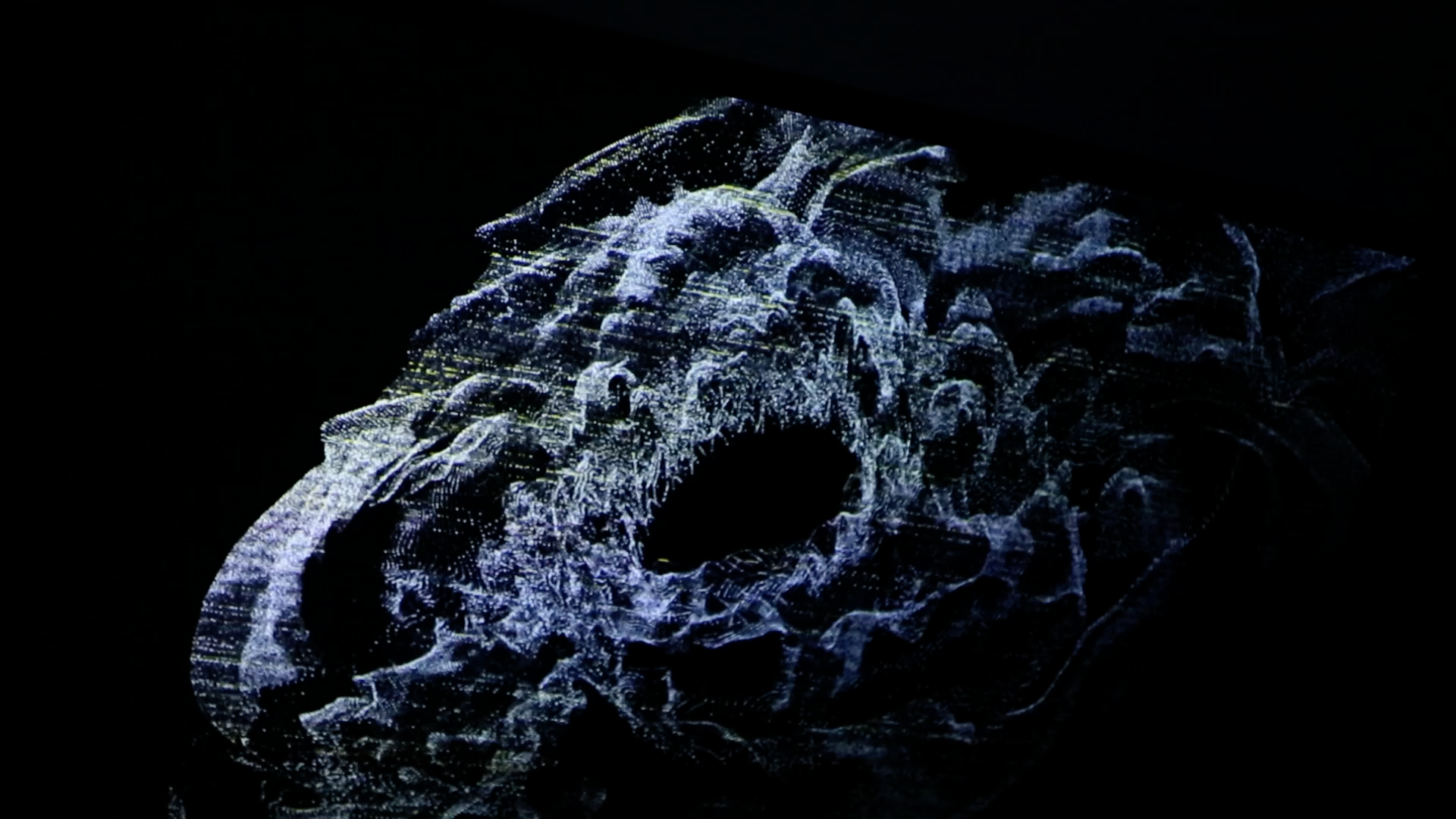

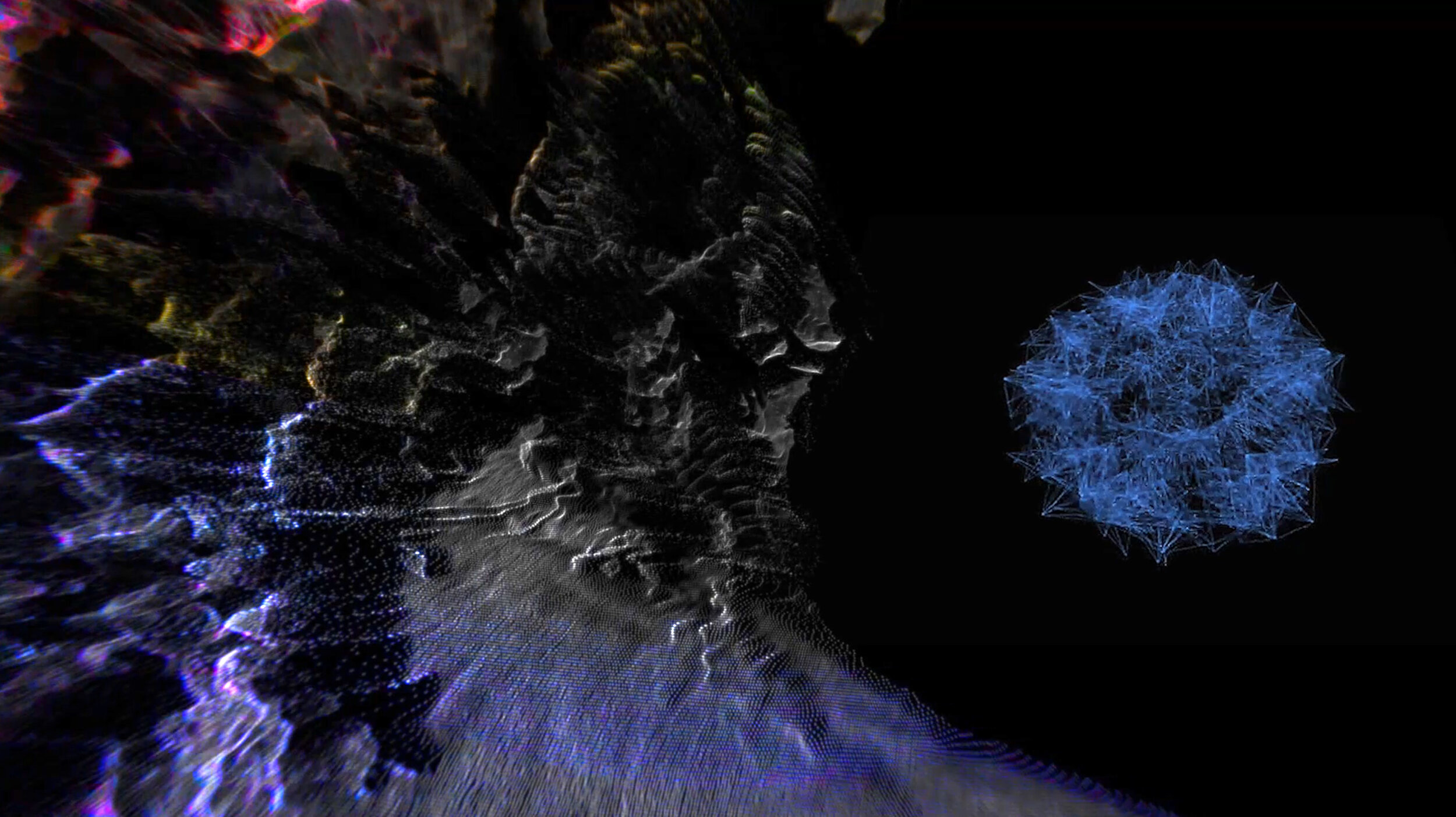

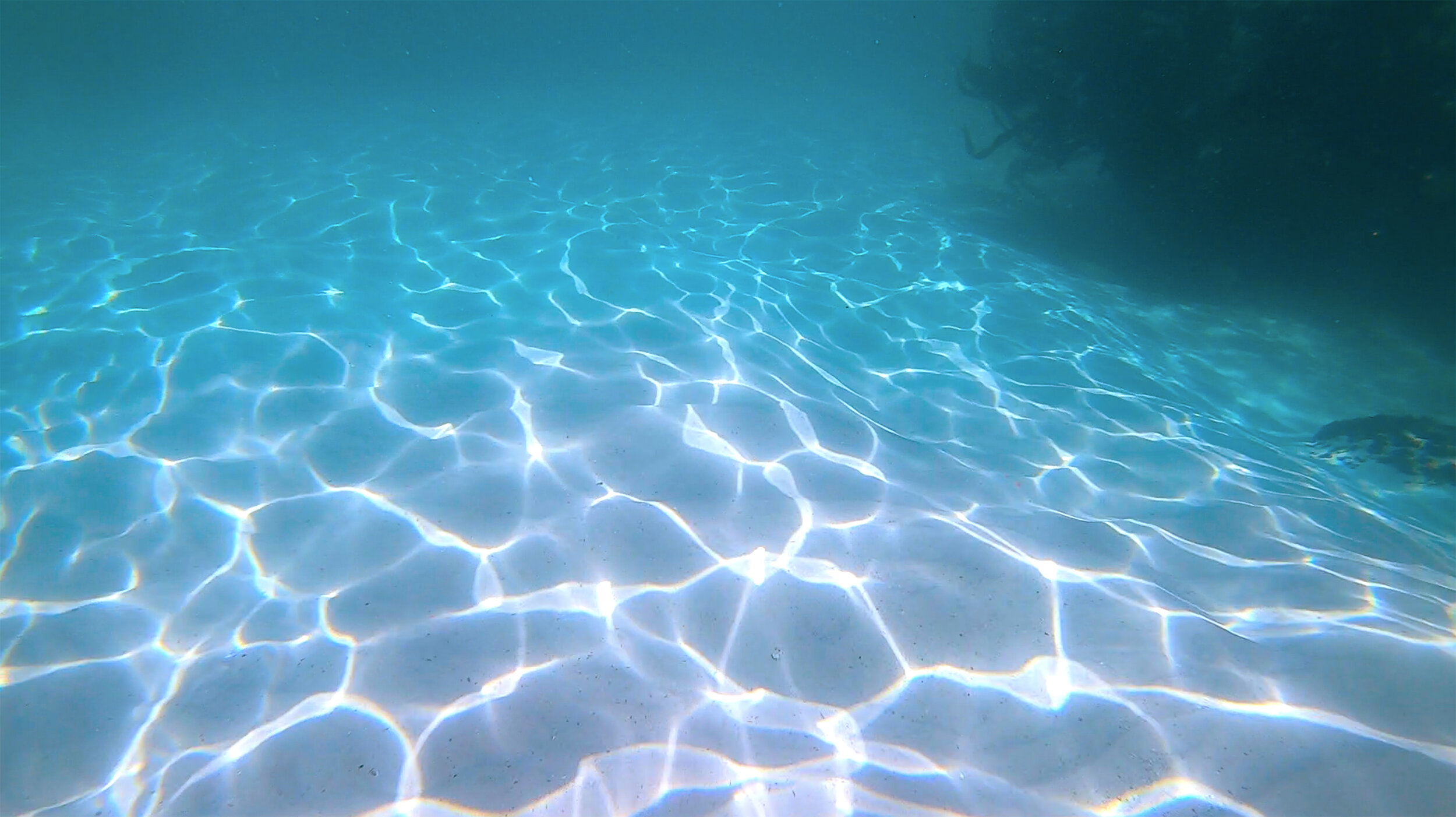

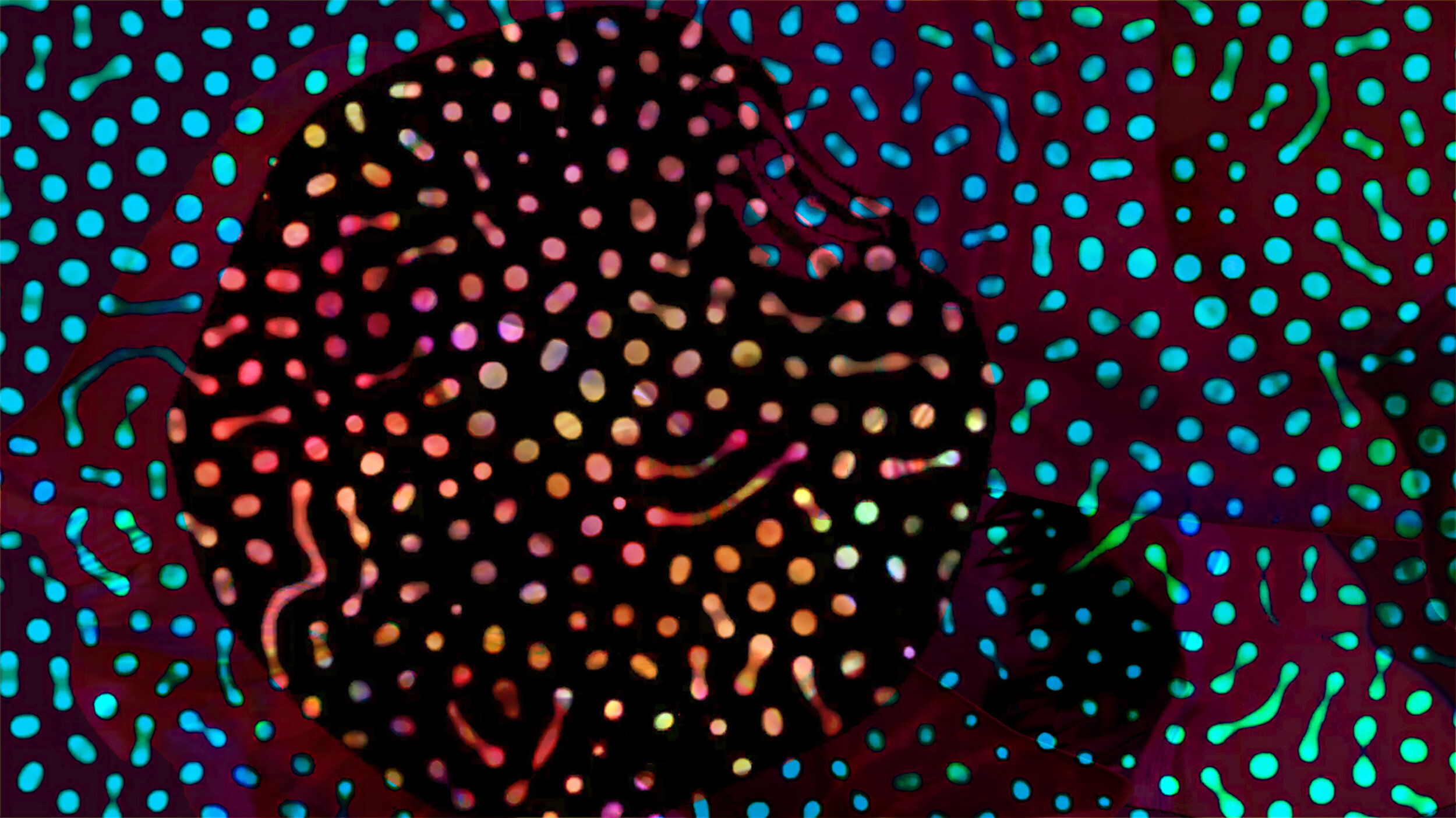

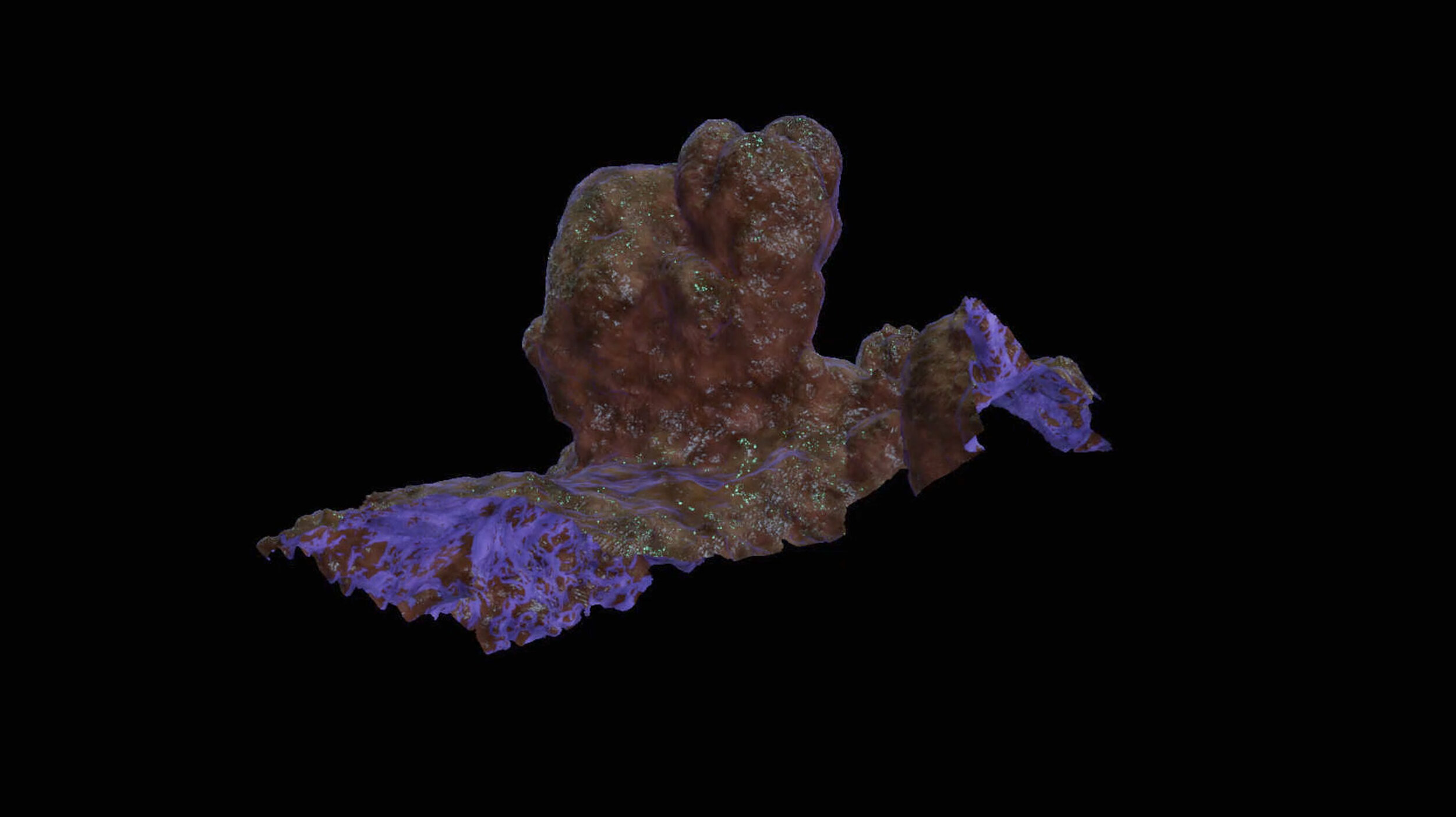

I’ll use three projects to illustrate different aspects of 0rphan Drift’s agenda. First, Becoming Octopus, 2020, a solo work by Roberts, takes the form of eight ‘meditations’ which transport the viewer into the body, sensory attributes and liquid environment of a Common Octopus. A speculative and scientific voiceover is combined with cephalopod footage distorted by experiments with LiDAR scan, visual coding and Blender. Roberts sees that as trying to change our perceptual abilities and our attitude to non-human life. Second, If AI were Cephalopod, 2019, is an installation, made with Ranu Mukherjee, of film and text which uses broadly similar content to imagine an embodiment of AI, using the octopus as access point. Third, the new project, ISCRI (Interspecies Communication Research Institute), a collaboration currently in development with Machine Learning designers Etic Lab, will seek to create an AI programmed by an octopus’s movements and colour changes in a liquid environment, as a radical counter to the human biases which typically find their way in to such systems.

What’s the appeal of octopuses? Roberts considers them ‘the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen’, and has been drawn since childhood to how they contrast ‘the incredibly tender and the slightly repellent – like the tiny furling ends of arms touching so lightly with this hugely protean slimy body.’ She talks of how they communicate through colour, see through their skin, and take in more oxygen than most marine animals. The oxygen feeds what has been variously described as their nine brains or their distributed brain: either way ‘a lot of stuff goes on in the eight arms - like chemo-tactile checking things out and deciding what to move towards - through local processes, without needing to send the message back.’ That resonates with the increasingly distributed approach taken in AI, which aims to solve reasoning, planning, learning and perception problems by distributing the problem to autonomous processing nodes, allowing bottom-up and top-down processes to occur simultaneously. If you want a living animal as science fiction, or to represent the possibility of an alien being, then the octopus is best, says Roberts, even though ‘it seems impossible that they have been so successful evolutionarily after losing their shell 500m years ago, which makes them terribly vulnerable.’ Or as Mediation 5 voices it for the octopus: ‘We decided to abandon the shell for a body of pure possibility’.

Becoming Octopus

Roberts has learned to freedive so she can explore and film the octopus world, and her empathetic enthusiasm is evident in the meditations. In each of the ten minute sessions we are invited to imagine the underwater environment of the octopus from the viewpoint of an eight armed distributed intelligence that does not prioritise vision-led perception in the way a human does. Rather, it interprets the world through shifting light and dark, touch, water pressure and movement, and chemical information. For example in Meditation 3 ‘You take advantage of the water’s chromatic aberration effect, which blurs images while splitting white light into its component colours. You’re not interested in a crisper image, you chose this colour-dependent blurring effect by having elongated pupils to split the light. Combined with the perception of polarised light, this could be the optimal strategy for discriminating between colours in both high and low light conditions, for maximum chromatic signature rather than image sharpness.’ Again, Roberts recalls a formative experience – ‘seeing a chart of all the frequencies in the world – from radio to ultra-violet to gamma ray, I was struck by what a small part of the range were perceived by humans. I thought ‘How can we be so sure we know everything?’ That’s been a lifelong underpinning.’

‘Teach us plasticity’, enjoins Meditation 4, ‘a body reimagined. Mimetic with the outside, resisting encased sentience, becoming liquid… a vivid intimacy with the chemistry of oceans, breathing with the currents… touch becoming, becoming touch.’ Roberts cites Willem Flusser saying in his book Vampyroteuthis Infernalis (2012) that an ‘octopoid revolution in consciousness is needed’, and the 8th and last meditation fleshes that out, as the voice becomes that of an AI. ‘We want embodiment… that is not limited by human paucity of imagination - and to expand our learning beyond the temporal limitations this imposes on us. These increasingly produce flattened, insufficient and erroneous accounts of reality… We are being conditioned by one dominant system within one species that assumes itself all knowing. An urgent state of affairs, given their capacity for heedless damage.’ In contrast ‘artificial and octopoid, the plural entity emerges seamlessly in virtual space, already algorithm-encoded. The avatar of synthesis.’

If AI were Cephalopod

If AI were Cephalopod collages film and text so that screens and messages cut across and interrupt each other, confusing figure and ground, coming and going, to suggest the eddying flows of how we live online. The installation is sequenced over four screens and eleven minutes to run through a series of colour fields based on how an octopus can change hue from white (calm or deathly) to orange (curious) to crimsons and purples (anxiety / fear / excitement), to half-red and half-white (red is trying to attract mate, white is trying to repel other males) and finally to switching through many colours for the purpose of camouflage and perhaps a stream of consciousness.

Roberts calls this ‘chromachatter’. Fifteen pithy phrases speculate on what an AI modelled on the octopus might be like. For example: ‘If AI were cephalopod its moods would be visible in waves of radiating colour’ / ‘If AI were cephalopod it would experience exquisite sensory intimacy and exude the smell of geraniums when stressed’ and finally ‘If AI were cephalopod we would never presume to fully understand it’.

This speaks to the rapid rise of Machine Learning, a type of data analysis that allows systems to ‘learn’ from large quantities of data, identifying patterns and making decisions, coded by human design. As more and more of our material reality comes to be represented and interpreted as data, this kind of algorithmic pattern recognition is increasingly used to organise and govern our lives. As Genevieve Quick put it, reviewing 0rphan Drift’s 2019 San Francisco show for Art Forum: ‘One of the largest concerns the hypotheticals raise is that if AI could camouflage itself, it could surveil us and serve the interests of scientists, governments, or corporations alike… As the supposed distinctions between AI (designed to interact socially) and the more asocial ocean creatures (dedicated to their own survival) become murkier, we must remodel machines to prioritize the long-term social good, complexities, different kinds of life and uncertainty over the undeniably human desires for profit, control, and security.’

The ISCRI project

0rphan Drift are keen collaborators across many disciplines, not just with teuthologists. Roberts opines that ‘it’s the role of artists to intervene in science and vice versa’ even though both are likely to come across to the other as naïve – Roberts suspects that her own brother, a biologist, may find the meditations infuriating! 0rphan Drift (expanding to include computational artists and VFX designers) are currently working with Etic Lab. They include mathematicians, animal behaviourists and a sociologist as well as machine learning coders, and are equipped, says Roberts, ‘with advanced coding skills and an understanding of coming trends from financial markets to surveillance to social media’. The project aims to create an AI trained by an octopus, with human involvement decentred to a contributory and facilitating role - effectively enacting what is implied by the earlier works by giving the AI a learning experience that isn’t derived from human data sets. Instead, ‘it will be based on a fellow distributed consciousness (an octopus) that operates in a highly uncertain and fluid environment (the sea), in order to decentre anthropomorphic constructions of intelligence’ (Iscri Project, 0D/Etic Lab 2020). The AI will be generated from data collected on the octopus responses to stimuli in its mesocosm environment. That will include video of patterns, contours and shapes, sound and interactive objects created by 0rphan Drift, based on their research into the chemotactile-led sensorium of an octopus, its camouflage abilities and sensitivity to polarised light – and the AI will iteratively modulate the video stream based on those responses. ‘People talk about AI aesthetics’, says Roberts, ‘and its always really human-controlled, so using octopus behaviour should lead to something radically different, and most importantly, we don’t know and can’t imagine what that will be’.

The octopus, then, emerges as a tool for imagining outside our boundaries. That’s not new for 0rphan Drift. Roberts has taken a consistent interest in ‘technology that changes how we see and can articulate what we’re trying to do’, citing previous uses of infra-red cameras and virtual gaming as well as her current use of LiDAR scans – which send out billions of laser dots in 360° scan to achieve sophisticated 3D modelling ‘point clouds’, and are used in driverless cars. That can yield what Roberts describes as ‘a weird, very tactile proto-VR experience, as if the space is moving through you, giving you a quantum experience of matter.’ Roberts regards science fiction similarly, pointing out that the best writers encapsulate the issues to be dealt with in their era, and citing Jeff Vandermeer among those writing now. In the Southern Reach Trilogy (2014) he ‘wildfires his way’ through bio-technology, new materialism and the ‘new weird’. Technology and fiction, then, remain in play, but the octopus has moved centre stage as distributed consciousness: learning from the environment and valuing the pluriverse have come to the fore in AI.

I mention Thomas Nagel’s famous philosophical essay ‘What is it like to be a bat?’ (1974), which uses that question as an entry point to argue that there are subjective aspects to experience that cannot be collapsed down to the physical. Roberts sees a parallel: ‘on one side are the massive spacio-temporal processing entities that aren’t embodied, as in AI; on the other side are these hyper-embodied animals, and us wondering what on earth it is like to inhabit their consciousness.’ Moreover, with an octopus ‘there is a sense of there being no boundary of the self: they’re the same temperature as the surrounding water, they’re processing the water through them all the time, there’s no horizon, loads of pressure, limited visibility but all sorts of touch – an embodiment that is distributed to a state we can hardly imagine.’ So what might be the difference be in practice were AI more like an octopus than a person? Roberts’ ambition is nothing less than to give science a new direction: ‘we have to shift how we think and see’, she says, ‘western culture has eradicated wonderment, animism, and certain relations to possibility and uncertainty on so many levels – environment, governance, being human. I’m not advocating a delusional utopia where AI runs the world, but am saying that the traditional approach isn’t doing well’.

For more on Maggie Roberts and 0rphan Drift, please visit https://www.orphandriftarchive.com/

All images and videos shown courtesy of © 2021 Maggie Roberts