MARIELE NEUDECKER: THE CONTEMPORARY SUBLIME

‘It’s hard to say where exactly the influence lies,’ says Mariele Neudecker (b.1965), while pondering to what extent her interest in science can be attributed to her upbringing. ‘There’s been a lot of things in my life that should have influenced me, but they didn’t’. Nevertheless, with a father teaching chemistry, biology and physics at the local secondary school, it is no surprise that the German-born artist has found herself working regularly with scientists and researchers, adopting their processes into her interdisciplinary works as she investigates the nature of perception and our relationship to landscape. Taking her cue from nineteenth-century Romantic artists, it is the search for contemporary manifestations of the sublime – both natural and technological – that drives her inquiries. From projects interrogating the awe-inspiring experiments at CERN, to deep sea explorations in the Indian Ocean and expeditions to extreme Arctic environments, Neudecker’s multidisciplinary practice is propelled by a relentless curiosity about the world.

‘When I was young, I spent a fair amount of time in the school’s labs with my father. I loved observing the experiments he tested out with me and my siblings,’ Neudecker recalls. He also showed her natural history films and demonstrated intricate anatomical models, such as the inner workings of the human eye. These formative experiences sometimes show up in her works. Take the mixed media sculpture 400 Thousand Generations, 2009, which comprises two glass spheres filled with water and salt that contain upside down models of mountain ranges. Appearing like improbable snow globes, these eyeball-like forms refer to the evolution of stereoscopic vision, alluding to the way that the eye sees the world upside down before the brain flips it upright. It addresses a central concern of Neudecker’s art: the limits of human perception. As she put it to curator and founder of Arts at CERN, Ariane Koek: ‘Everything we look at is mediated, screened, cropped and framed in different ways by our eyes, our senses, our technology and the environment: we can never ever truly see the thing itself in its entirety’.

Neudecker came to prominence in the 1990s with her ‘tank works’ – intricately crafted landscapes in glass tanks that, through a careful balance of fibreglass, chemicals, water and lighting, channeled the nineteenth century Romantic sublime. These miniature environments feature model mountains, forests and ice fields, all submerged in liquid to replicate a range of atmospheric effects, such as mist and fog. The hazy dioramas, which gradually change over time, reimagine the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) and others, prodding at idealised notions of landscape and revealing them to be constructs. These heavily mediated, hermetic versions of reality initially drew from reproductions, photographs, paintings and other secondary sources. It was only a matter of time before Neudecker ventured out into the landscape itself, to have the kind of subjective experience of nature that was so fundamental to the Romantics.

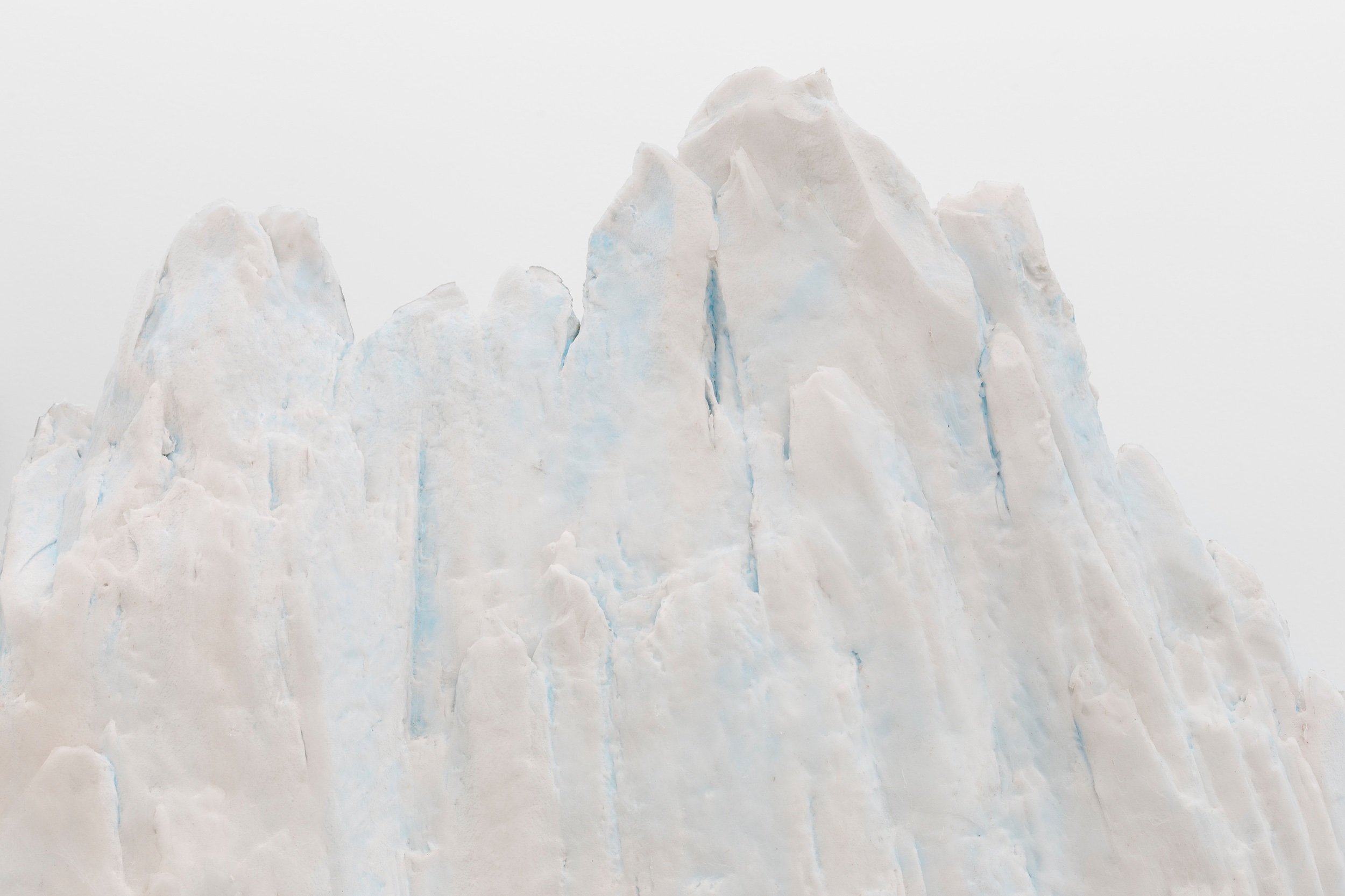

In May 2012, Neudecker took a five-week expedition to the barren landscapes of north west Greenland, visiting Arctic field stations and travelling on dog sleds with subsistence hunters. Her aim was to escape the trappings of modern life and discover whether ‘pure nature’ can still be found. The trip proved to her that wilderness simply doesn’t exist, ‘because everything is saturated by culture in some way.’ She also witnessed firsthand the effects of climate change, noting that the Inuits have lost three months of hunting time due to the warming climate. Works created in response included an iceberg sculpture There is Always Something More Important, 2012. Finely crafted from fibreglass and stunning in its verisimilitude, the sculpture reduces the vast hunk of ice to human proportions, alluding to the damaging impact of our modern lifestyles on these fragile environments.

Whilst climate change is an evident concern of Neudecker’s recent works, she stresses that her sculptures, videos and installations are not platforms for environmental politics. ‘Artworks are not propaganda tools,’ she says emphatically. ‘Of course, I am thinking about current questions and politics when I make these works, and inevitably the iceberg piece confronts viewers with clichéd images of climate change, but art audiences don’t need their lack of awareness pointed out to them. Still, it is important to intrigue, inspire, and maybe even agitate people.’ This is reflected by the ambiguous play on words of the sculpture’s title. ‘There are so many situations where it is very difficult to not drive, not to have kids, not to eat meat,’ she explains. ‘All sorts of exceptions are made, because there always is another reason, always something more important. Or is it that climate change is more important?’

Neudecker’s tank works were not conceived to reference climate change; when she began making them, the subject was barely on anyone’s agenda. Today, however, these submerged worlds appear as deathly portents of poisoned, underwater futures. As Pontus Kyander writes in ‘Sediment’, the recent monograph on Neudecker’s work: ‘The early 2020s are different times where other discussions have taken a priority. In the wake of climate change, our perceptions of “nature”, “landscape” and “trees” have also changed. [Neudecker’s] work is now less entangled in ideological intricacies and post-Romantic discourse, and instead more with matters of survival in an age of seemingly overwhelming threats’. A case in point is And Then The World Changed Colour: Breathing Yellow, 2019. Commissioned for the mausoleum of London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery, it presented a forest submerged in an acrid yellow environment, evoking catastrophic environmental breakdown.

‘I am positively intrigued about subjective readings of my work,’ Neudecker says. ‘Originally, the tank works were about perceptions of space, time and an understanding of images – how we look at things and understand or read them. The most recent tanks inevitably have more to do with issues around climate change, but this is just a part of the work, never its purpose.’ Similarly, the issue of rising sea levels had nothing to do with The Sunken Village / Das Versunkene Dorf, 2001, Neudecker’s life-size installation of a drowned village in the Tiggelsee/Steinfurt artificial lakes near Münster in Germany. Though initially evoking the lost villages of the Derwent Valley and other sites submerged under reservoirs, today it is hard not to see this remarkable project in terms of ecological anxiety. ‘I am interested in questioning and possibly re-calibrating our understanding of the world in a wider sense, and, of course, politics around climate change are part of that,’ she says. ‘I see art as an opportunity to let others look through my eyes, not to tell them what to see. What people make of it is up to them’.

Submersion has been a significant, if understated, aspect of Neudecker’s art since the 1990s; one of her tanks, Shipwreck, 1997, even approximated a seafloor view complete with a decaying vessel. It seemed inevitable that the actual ocean would eventually enter her work. ‘I thought she might be interested in the unusual and distant context of the deep sea,’ writes curator Alice Sharp in her contribution to ‘Sediment’. In 2012, after hearing a talk on overfishing by Oxford University marine biologist Alex Rogers, Sharp suggested that the two might develop a collaboration for the commissioning organisation Invisible Dust, which brings artists and scientists together to explore environmental concerns. Rogers was heading a research team that sailed aboard the RRS James Cook to study damage to seamounts in the southwest Indian Ocean. His research into the impact of deepwater fishing is largely conducted using Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROV) filming at a depth of 1300 metres and below, and it was this video footage that inspired several of Neudecker’s works.

Rogers provided her with an extraordinary 16 terabytes of film. ‘I looked though all of it, which took many days, weeks actually,’ she explains. ‘It became very clear very soon that I was intuitively selecting sections devoid of visible life: landscapes with abandoned residues of human activity in them, such as dumped fishing equipment – old lobster pots, nets, ropes etc.’ These scenes appear in Horizontal Vertical, 2013, a five-channel video installation. Some screens show evidence of illegal fishing, with seamounts damaged by nets dragged along the seabed, while another shows a ‘ghost net’ – an abandoned fishing net that can entangle and harm all manner of marine life. The installation highlights the devastating destruction of vulnerable marine ecosystems due to overfishing and pollution, but also how technology can limit as well as enable perception. ‘I was very interested in how the visibility of anything at that depth was limited to the shaft of light from the ROV,’ she says. ‘It became another extension of our limited perception: starting from the brain, then the eyes, the lens, the shaft of light and the view, with the layers of nerves and cables and the ROV connecting it all in between’.

Another work to emerge from this collaboration is the multichannel video installation The Improbable Always Happens Sometimes (1/2), 2017, which was first exhibited at Hull Maritime Museum in the 2017 exhibition ‘Offshore: artists explore the sea’. This time footage was used from GoPro cameras mounted to the outside of a Nekton submersible, recording a deep dive off Bermuda with Rogers on board. As well as the ocean’s depths outside, the cameras captured the scene inside the vehicle. In Hull, the installation was shown across two of the museum’s circular turret rooms. In one, a ring of monitors showed raw GoPro footage of Rogers’ descent while in the other room, viewers watched his ascent back to the surface on another cluster of screens. In the museum’s fishing collection, a display video stills from the submersible’s journey and two vitrines filled with drawings, paintings, lenses and miniature LCD screens demonstrated the connections and tensions between lens based and handmade images in Neudecker’s practice, as well as pointing to our limited knowledge of the ocean’s complex ecosystems.

The Improbable Always Happens Sometimes (1&2), 2017. Multichannel GoPro HD video on 6 monitors. Duration: 12’00” and 45’49”. Commissioned for Offshore by Invisible Dust in partnership with Hull Culture and Leisure. With support from Bath Spa University and with thanks to Nekton, and Alex Rogers, Professor in Conservation Biology, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford. © Mariele Neudecker. www.nektonmission.org

Pollution, whether in the sea, on land, or in the atmosphere, is a major concern for those tracking its environmental impact. At CERN, a special cloud chamber is used to study the possible link between galactic cosmic rays and cloud formation. Led by scientist Jasper Kirkby, the CLOUD experiment reproduces specific, often pre-industrial air conditions – virtual atmospheres that help build an understanding of atmospheric change over time and the role of greenhouse gas emissions and cloud formations. The project intrigued Neudecker, who has been visiting the world leading science laboratory since 2015 as Guest Artist on the Arts at CERN programme. ‘The scale of it all was very overwhelming,’ she says, ‘but the one thing that fascinated me the most was the fact that everything they are researching there is imperceptible to the human eye. The experiments are all re-enactments and representations of other things that have either happened in the past or are predicted for the future’.

Although the scientists Neudecker has worked with have all been very generous with sharing their knowledge, she soon realised that she would never truly understand the complexities of quantum physics, or the inner workings of CERN’s machines, and chose instead to focus on their exterior structures and material paraphernalia. Covered with tinfoil, plastic, tape and cables, the haphazard appearance of many machines seemed to contradict the sophisticated science experiments happening inside. For the video installation Everything Happens Once, 2020, Neudecker filmed the chambers, tubes and wires of the CLOUD experiment in a series of slow tracking shots. The footage is shown on two monitors that move horizontally left and right along parallel wall-mounted tracks, the screens travelling at the same speed at which the video was filmed. The effect is disorienting, much like Neudecker’s own experience of visiting CERN. ‘What also seemed totally relevant was that it was the one experiment that has some direct influence and responsibilities for policies and laws around Climate Change,’ she adds.

Another CERN project to have inspired Neudecker is the ALICE experiment, a 10,000-tonne detector which measures photons as they fly out of the molten hot plasma created in collisions at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). Wanting to capture its scale and complexities, she juxtaposed tracking shots of the detector with closed caption descriptions of the unique mechanism of human vision from a presentation that Professor Alan Litke of the University of California gave at CERN. ‘The four detector points on the LHC function like large technological eyes,’ explains Neudecker. ‘I knew that the deliberate clash between my film and Litke’s words would set up a great collision of two worlds’. Titled The Eye [A.L.I.C.E. A Large Ion Collider Experiment v1], 2021, the video was premiered in the V&A’s 2021 exhibition ‘Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser’, inspired by Lewis Carroll’s timeless stories. It demonstrated how CERN’s search for the unknown is taking scientists deeper down the quantum rabbit hole, altering our perceptions of reality itself.

CERN is a natural home for inquisitive artists like Neudecker, whose work continues responding to its awe-inspiring environment. Heart of Darkness, 2021, is one of several digital drawings made during the national lockdown in which she added tangles of improbable cables to images of obscure scientific equipment. Though these images seem miles away from the tanks that made her name, she sees things differently: ‘I am not sure if these digital drawings are that far removed from what I was doing with romantic landscapes,’ she ponders. ‘To me, they are a different kind of landscape: the technological sublime’. As with her earlier tank works, these too, on closer inspection, reveal themselves to be constructs. From Earth’s remotest bounds to the outer limits of scientific inquiry, it seems that Neudecker has travelled full circle.

Mariele Neudecker: Sediment is published by Anomie.

All images and video shown courtesy of the artist © Mariele Neudecker.